Interstate Surveillance and Bodily Autonomy in Amarillo

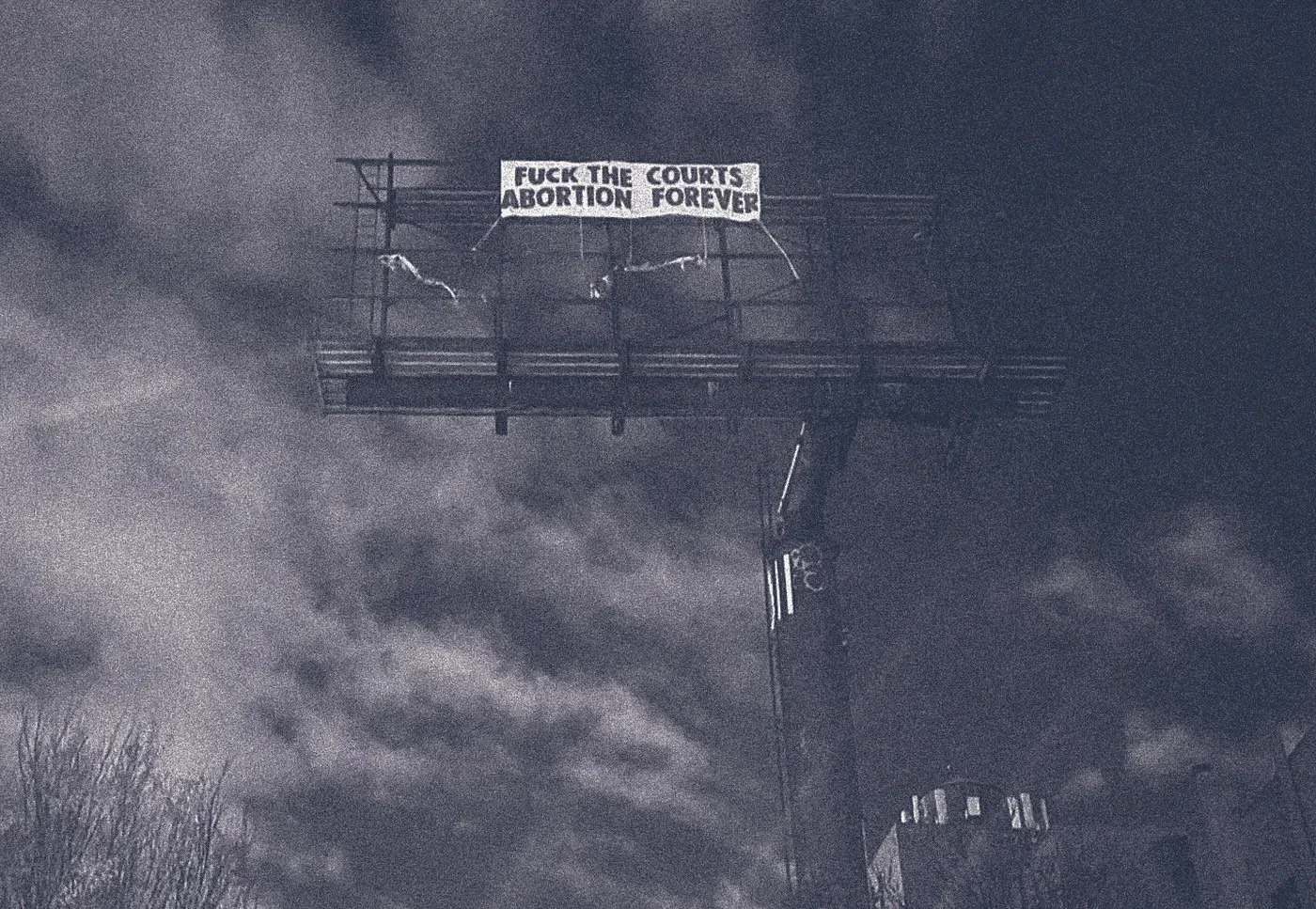

Banner on billboard above Brooklyn Queens Expressway, Brooklyn, NY, April 2024.

This is an article of my graduate research completed in May 2024.

Attached to two windmills at the entrance to a highway rest stop, posters display a line drawing of a white Texas Ranger with a chiseled jaw. A banner above his hat and the Texas state flag reads: “THE EYES OF TEXAS ARE UPON YOU!” Below his collared jacket and aviator sunglasses is a clear instruction: “CELLULAR PHONE USERS call 911 to report criminal activities or emergencies.” The rest stop is under surveillance by eight different armed state agencies.1 Inside the women’s restroom stalls, trafficking notices line the walls. Widespread panic over sex trafficking, bolstered by vague statements from the US Department of State and the Department of Justice, as well as an extremely well-funded rescue industry with deep ties to the Christian Right, purport that sex traffickers lurk around every corner. Investigative reports have revealed these claims are unfounded.2 Still, the mythical sex trafficker looms, and systems of white and Christian supremacy, misogyny, and class oppression undergird the monitoring of the rest area. In the rest stop atrium, a map references Commanche Medicine Mounds, an RV park, and Family Dollar. Several other posters depict a young white girl menaced by traffickers. She hangs her head, sad, sullen, and alone, ashamed of the sex she was coerced into because of her low socioeconomic status, scarred by assault and the abortion she was forced to have to continue selling sex. She needs you, rest stop visitor, to recognize her among your peers—or in the mirror. The Texas Rangers will restore her bodily autonomy.3

An hour further along US Route 287, there are no public rest stops, just two gas stations. No trafficking notices line the Sunoco women’s restroom, although it is marked as wheelchair-accessible. The wheelchair-accessible stall, however, is crowded with baby furniture. A weathered wooden chair is positioned to the left to pacify a wailing toddler or support a breastfeeding mother. A bassinet to the right of the toilet doubles as a changing table and crowds the stall to the point of inaccessibility for an able-bodied person, let alone someone in a wheelchair.

Here, women are presented as having bodily autonomy; they are free to be mothers.

The paint has worn off the floor along the path to the toilet. Many people traversed it, observed the stall’s configuration, and internalized motherhood as the only supported disability. Nearby, trucks audibly hum along the four-lane interstate. The highway hugs the rolling topography, and bright white clouds appear against an endless, cerulean sky. The road through this part of Texas maps fluidity and freedom—for white, God-fearing, heterosexual men.

Highways exist to invoke order and maintain control.4 Most American roads were constructed before the twentieth century. Since then, the quality and capacity of interstate systems have been the focus of highway infrastructure, according to world-renowned landscape and road ecologist Richard Forman.5 As has become increasingly clear in recent years, the same regulatory systems that monitor our roadways monitor the bodies of those who can become pregnant. Motherhood is not compulsory for people with uteruses, but the design of modern American highways, in tandem with our reproductive health policies, suggest otherwise. Interstate highways reflect "settler geographies and ontologies," writes critic Deena Rymhs.6 The system of travel romanticized in On the Road fosters a fabricated, ordered freedom with a violent, raced, and gendered history.

Women, girls, and non-binary people are traveling farther to access reproductive care under state abortion bans,7 often along highways heavily policed by state officials who, as the non-partisan research institution, the Guttmacher Institute, states, "disproportionately target marginalized communities" faced with the threat of criminalization through the "misuse of existing laws." 8 It’s uncertain how long interstate travel will remain viable as new abortion travel bans proliferate in Texas cities. These travel bans layer local surveillance on top of heavily state-surveilled roads. The construction of American interstates themselves overwhelmingly and negatively impacted the poor and people of color. 9 As a design object, highways have long determined who lives and dies. For pregnant people fleeing Texas towns, that historical significance has a renewed meaning.

I am returning home to Amarillo, Texas, on guard, fearful not of traffickers but of watchful neighbors. Here, my destiny as a white woman is predetermined. I am a survivor in several senses of the word, but what feels prescient is that I survived Amarillo. Here, the term “survivor” is increasingly applied to young adults and children who have survived the “abortion holocaust.”10 It is a sly way to cast white people as existentially threatened by national genocide, as the would-be victims of a secular and increasingly multiracial society that undermines the established order between men, women, the nuclear family, and American religion.11

Just within Amarillo’s city limits, a billboard reads: "PROHIBIT ABORTION TRAFFICKING." It’s intended to imitate a government roadway alert, but the white sans-serif font on a field of solid crimson reads more like a cheap beer advertisement. Not long after January 6 attendee Mark Lee Dickson introduced an abortion criminalization campaign to the Amarillo City Council in 2023, these billboards appeared near major highway exchanges.12 A self-proclaimed “millennial missionary,” Dickson’s legislation proposed to turn Amarillo into a sanctuary city for the unborn.13 Not to be confused with asylum extended to international refugees, Dickson’s ordinance proposes to ban abortion from the moment of conception, with no exceptions, through a private citizen bounty mechanism.14

Dickson, a white, wide man with a severe chinstrap and backward baseball cap, has successfully passed similar ordinances in sixty-nine other cities within the last five years.15 His ordinance bans the transport of pregnant people across state lines to receive reproductive care and the travel of non-residents passing through cities to terminate pregnancies in another state. Amarillo is a vital metropolitan target for his ordinance campaign. This city is, Dickson says, a “hub for abortion trafficking,” with two major US thoroughfares connecting North and South, East and West. Interstate 40 runs from North Carolina to California, US Route 87 from the Canadian border to Mexico, where there’s a cottage industry of abortion providers.16

I reached out to Dickson for an interview. He declined to meet me at his campaign headquarters in Amarillo but offered to meet me in Lubbock, where a Sanctuary City Ordinance was passed late last year.17 “I would be glad to share with you the work we are doing in Amarillo and across the State of Texas,”18 his note began in friendly enough terms. But an easy Google of my name might have led him to the awareness that my years of work funding reproductive justice could be criminalized in Lubbock; meeting there put my bodily autonomy in jeopardy. I countered with an offer to meet over Zoom, to which he never replied.

Dickson’s extreme abortion bans are presented as interventions that make Texas cities safer for mothers and children, but historical and current US and global data demonstrate abortion bans endanger the lives of children and mothers.19

At the heart of Dickson’s legislation is not care for women and unborn children but a yearning to take over the regulatory power highway design manifests.

America’s first iteration of the interstate was a road of rolled crowned stone that stretched from Maryland to Ohio, measured 30 feet wide, and cost $14,000 a mile.20 Post-independence, state and federal governments were largely uninterested in costly road production and instead invested in railroad expansion. Until the federal government developed a network of national postal roads at the turn of the twentieth century.21 Contraceptive distribution from rubber vendors and dry goods stores proliferated along federal postal roads.22 Anti-vice crusader Anthony Comstock was commissioned by the United States Postal Service as a special agent in 1873 to prohibit the distribution of birth control and women’s health literature along US postal highways.23 Instantaneously, roads used to transport goods became a weaponized tool to manage and surveil women.

The Comstock Act was never repealed. It is mentioned through legal citation numbers and sometimes in name in Dickson’s sanctuary city ordinances. Comstock’s use of the highway as a “straightening” technology, a federal government tool, gives Dickson’s ordinances maniacal power. “These laws are not explicit abortion bans, but ‘de facto’ abortion bans. They require compliance with federal statutes prohibiting the mailing and receiving of abortion-inducing drugs and paraphernalia,” says Dickson.24 This means not only is interstate travel along highways criminalized—in which pregnant bodies become the banned substance traveling along roads—but the sending and receiving of abortion pills through the mail is also criminalized. The use of Comstock to regulate abortion, particularly medication abortion, the most predominant form of abortion care method in the United States today, jeopardizes the few remaining pathways pregnant people have to access reproductive healthcare today.25

Wider interpretations of Comstock could go further to target clinics providing surgical abortions underground or in instances of emergency. David Cohen, a professor of law at Drexel University, says the Comstock Act would prohibit the mailing of abortion-inducing drugs, as well as operating room tables and speculum and suction cannulas and every instrument used in an abortion.26 In conjunction with the prohibition of medication abortion, the banned distribution of surgical tools would make the operation of an abortion clinic impossible. Legal scholars largely consider Comstock to be anti-democratic because it was passed at a time when women were unable to vote and excluded from public life. But it is the anti-democratic means of surveillance Comstock embedded into the regulatory nature of highways and the goods and services transported along them through which Dickson has built a much larger national plan. Increasingly, headlines describe the Comstock Act as the nation’s back-door abortion ban.27 Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas demonstrated a preference for its revival at a recent Supreme Court hearing in March. The case before them originated in Amarillo and relies on Comstock to overturn the Federal Drug Administration’s approval of mifepristone, a drug used in medication abortion.

When Anthony Comstock began enforcing his anti-obscenity laws in 1873, the official census record for US citizens in the Texas Panhandle was zero.28 In 1916, when the United States expanded its network of postal roads through the first federal highway act,29 Amarillo had just incorporated as a city established by Confederate soldiers.30 The first birth control clinic in the United States opened by the end of the year and was shuttered within ten days under Comstock obscenity charges. 31 By the seventies, birth control was used and supported widely by many Americans, but this was not the case in Amarillo, a city built as a transportation corridor around railroads and federal highways.32

Getting adequate reproductive healthcare in the Texas Panhandle proved difficult, even after Roe passed. Oral histories of women in local museum archives paint the picture of a medically underserved community attended to by a band of volunteer, misogynist, racist doctors. In an interview with Karli Dye, the founder of Planned Parenthood of the Texas Panhandle, Dye recalls having as many as eighteen offices in the twenty-six counties of the Texas Panhandle for four years following Roe. All of the offices were heavily picketed, and Pattilou Dawkins, Chair of the Board at that time, describes federal funding stipulations that required clinics to provide abortion access, but “there wasn’t a doctor in town that would do one.” To even get women birth control into the eighties, Dye stressed the importance of getting the “right patient to the right doctor” to circumvent physician bias of a patient’s race, age, or marital status. 33

Some interviews mention mothers who threatened to end their lives if denied an IUD. Most women interviewed believed abortion was a sin, but they also believed it was a healthcare service that should be provided. One Planned Parenthood volunteer referred to a condom as a condiment, and many found their way to Planned Parenthood through advocacy work with the local cancer center.

Panhandle women fought for basic reproductive freedoms commonplace in the rest of the country while the government constructed a concealed nuclear weapons plant.

Amarillo is ostensibly a military colony; its economy is dependent on the continuation of the nuclear arms race.34 On Interstate 40 and US Route 87 trucks transport unmarked shipping containers to Pantex, the only production facility for assembling and disassembling atomic bombs in the United States.35 In the weeks following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States government dispossessed 16,000 acres of land outside of Amarillo by right of eminent domain.36 Government planning documents and census records suggest the Panhandle was chosen for nuclear weapons manufacturing because it was “barren” and “empty.”37

An interview transcript with a prominent Texas highway engineer, Pete Gilvin, characterizes Panhandle road construction as intermittent until December 7, 1941. Gilvin recalls that once the United States entered the war, “the only highway work done had something to do with the war effort.” 38 After World War II, Pantex briefly closed but reopened after the Soviet Union’s successful nuclear weapons test.39 By 1953, Gilvin went into business for himself because military roadway infrastructure contracts were so plentiful.

By the sixties, Amarillo shifted from an all-white enclave to an increasingly diverse community, thanks in part to Pantex, who employed a sizeable portion of women and “minority workers” during the Cold War.40 Over subsequent decades, President Eisenhower’s National Interstate and Defense Highways Act transformed postal roads and interstate highways into a superstructure of 42,000 miles of militarized roadways designed to transport weapons and tactical equipment,41 and Amarillo became a community that built a culture out of the surveillance of its highways.

Pantex continues to grow today, now situated on 18,000 acres, 42 complete with 650 on-site buildings that store plutonium cores and nuclear waste.43 Earlier this year, the largest wildfires in Texas state history headed toward Pantex.44 This briefly made national news. Noticeably, reporters did not ask what would happen to Panhandle residents if the nation’s stockpile of nuclear weapons detonates. Would Panhandle residents be safe? How many would be impacted?

I understood the choice not to ask these questions as an admission that our annihilation would not matter.

The federal government had long calculated that we were a necessary sacrifice in case of an emergency. This is a reality that defines the existence of women in the Panhandle and increasingly defines the reality of pregnant people in the rest of Texas and the United States facing abortion bans that similarly dismiss their humanity.

The United States government asks Panhandle residents to give up bodily autonomy in the name of the nation like the Evangelical faith tradition asks believers to give up ownership over their bodies through the divine process of sanctification. Amarillo has been a Christian community since its founding. The overwhelming majority of Amarillo’s three hundred congregations today are Evangelical and Baptist.45 Waves of church growth mirror the expansion of the American war machine.46 It’s difficult to ascertain what came first, the bomb or Amarillo’s notch in America’s Bible Belt.

Dickson refers to Amarillo as an abortion trafficking hub run by “baby murdering cartels;”47 referring not to the US government as a murderous cartel, annihilating innocent babies with the bombs it builds or the workers it poisons just outside Amarillo city limits, but referring to Amarillo’s design as a transportation corridor—a metonym for an American city on the hill threatened by xenophobic rape and molestation through mixed-race fornication and immigration.48 Dickson seeks to counter this “invasion of the body of the nation” through the control of the white woman and child through total abortion bans. Should he and his allies gain control over the regulation of highway infrastructure, a design system that embodies the ideology of American nation-building, grave danger lies ahead.

Dickson’s blend of Christian white supremacy mediated through highway infrastructure would strengthen pre-existing necropolitical systems, quietly and out of view, particularly in an expendable place like Amarillo.

Comstock is repeatedly referred to as a “zombie law” in the media, a piece of Victorian-Era legislation revived from the dead by the far-right. But, as a designed system tied to highway infrastructure, Comstock’s oversight and influence never left, which is why its reemergence has been so swift. An isolated interrogation into contraceptive access in the Panhandle reveals an interesting correlation between the staying power of restrictive reproductive policies in a region where there are more miles of highway than people.

The last Planned Parenthood in the Panhandle shuttered a decade ago, widening an already profound reproductive healthcare gap. Amarillo has one remaining private reproductive health clinic, Haven Health. It is nestled behind the country club across from a gated community. Haven lost its ability to offer contraception to minors in 2021. Jonathan Mitchell, the architect of Texas’ statewide abortion bill and a close collaborator of Dickson, challenged Haven’s Title X right to prescribe contraception without parental consent. A Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a federal judge’s ruling in Amarillo in favor of Mitchell’s Title X challenge. As a result, family planning clinics across Texas are now banned from providing birth control access to minors without parental consent. 49

Claudia Stravato led Planned Parenthood of Amarillo and the Texas Panhandle from 2000-2011. The state had already launched a widespread campaign to defund Planned Parenthood by the time she joined the organization. She insists in her raspy Southern drawl beneath deeply furrowed brows and a crisp collared shirt, “We never offered abortions. It wasn’t socially accepted.” Claudia is the daughter of a Baptist minister. Her own support for abortions has limits, and still, she and her late husband survived arson and death threats for providing basic reproductive healthcare access. Claudia’s grandchildren were taken out of Catholic school and brought to Planned Parenthood by Father Yanta, who hosted weekly demonstrations to pray for the lives their grandmother corrupted.

“My Daddy preached on the East side. He helped folks in poverty. They wanted me killed for doing the same thing. For giving young girls birth control to have a say over their destiny.” Claudia’s time at Planned Parenthood took a toll on her health and her life. She began teaching four Texas State government seminar classes in the Political Science Department at West Texas A&M University as a form of retirement. Well into her seventies, Claudia tirelessly takes on a full load as her own ministry to get her students to pay attention to the changing laws around them.

Since Dickson proposed a sanctuary city ordinance to the Amarillo City Council last year, organizers with Abortion Access Amarillo report that requests for abortion travel assistance out of the state have ground to a halt. Afraid to implicate family members and friends or criminalize themselves, pregnant people are seeking abortions completely alone in states where abortion remains legal, praying the GPS location of their phones and vehicles are not tracked by state authorities.50 In the face of such extreme restrictions, more and more people are choosing to self-manage their abortion.51 This method of healthcare is also surveilled and criminalized. Dickson’s Amarillo ordinance prohibits the disposal of fetal tissue, even if pregnant people don’t utilize highways to obtain care.52

The potential expansion and enforcement of Comstock is at the forefront of present federal discourse, but its pervasive force shaped the Panhandle, transitioning from highway surveillance to an entire surveillance apparatus that operates on and off the road. A collective of radical young women organizing for reproductive justice is determined to fight back. So far, they have successfully thwarted Dickson’s efforts to legalize this de facto apparatus. They call themselves the Amarillo Reproductive Freedom Alliance (ARFA), an intentionally neutral name to galvanize white women targeted by Dickson’s ordinances that they need on their side.

ARFA’s resistance efforts pushed Dickson’s ordinance to a petition. He has since submitted twice the number of required signatures needed to force the petition to a vote. ARFA has met with City Council members individually for months to dissuade the council of all white males from adopting the ordinance and petition. At one point, it was rumored that Amarillo Mayor Cole Stanley was not opposed to a total abortion ban. He’s simply opposed to passing one drafted by an outsider. Whether Dickson’s ordinance passes through an upcoming council vote or the Council and Mayor decide to draft their own ordinance under mounting public pressure, the women of ARFA combat a culture of institutionalized misogyny and surveillance pervasive at local and state levels.

Grasping the many invasive limbs of this legislation’s implementation is daunting. “We will continue to regroup and change tactics as needed to prevent these men from taking complete control over our lives, but it’s terrifying,” they told me, gathered together around their insignia of a budding stalk of wheat against a starry Texas sky. The women of ARFA are determined to look out for themselves and their community through whatever visual means necessary. Through the use of local speech and agricultural symbols commonly associated with fertility, they are methodically pushing back on the lack of bodily autonomy that has become culturally pervasive over time.

Formed at a mega-church protest a year ago and strengthed through drag brunches and banned book readings, the women are reclaiming Amarillo, a city long been regarded as too entrenched in conservatism to be saved. They are risking their safety not for attention or moral superiority but because they simply want autonomy over their own bodies in the place they call home. The local conversation surrounding bodily autonomy is most visible through “prohibit abortion trafficking” billboards along the highway. This suggests something about the highway's mediated role as a continued extension of government enforcement and regulation.

The anti-abortion movement has long used the highway and the access it portends as a strategic affront to thwart abortion access. They have done so with considerable success and increasingly with federal and state government dollars—a model provided by segregationists who united under the “pro-life” umbrella during the civil rights era. In the wake of the civil rights movement, segregation academies lost their tax-exempt status.53 Racists had to find new defensible manifestations of whiteness at the same time Roe legalized abortion.54 Contraception and abortion access lowered the white birth rate as non-white immigration increased in the 1970s. Suddenly, racists and anti-abortion activists, white conservatives that previously coalesced around separate but complementary priorities, colluded around a common cause and found a way to use federal infrastructure dollars to protect white life at a discounted price.

Under the auspices of eminent domain, the federal government dispossessed communities of twenty million acres of land to build defense installations.55 Segregationists then used eminent domain as a tactic to construct highways that decimated non-white life. Robert Moses, a post-World War II preeminent urban planner, deployed “massive infrastructure elements—multi-lane roadbeds, concrete walls, ramps and overpasses—as tools of segregation, physical buffers to isolate communities of color.”56 In his 2002 report, “The Interstates and the Cities: Highways, Housing, and the Freeway Revolt,” historian Raymond Mohl estimates at least one million Black people were displaced through these infrastructure opportunities funded exclusively by the federal government.57 Ginger Strand, author of Killer on the Road: Violence and the American Interstate, describes this period as a “chapter in the nation’s history of racial conflict…where Jim Crow stepped behind the curtain and emerged in a new guise: infrastructure.”58 Put frankly, post-war infrastructure brutalized oppressed communities and extended the infrastructure of American white supremacy into the modern-day.59 Organized around federally funded mechanisms of segregation was the anti-abortion movement’s explicit flavor of white supremacy: crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs).

Dr. Jennifer Holland, an abortion historian, explains that there is a deliberate logic to where CPCs are located. CPCs are near highways, in demolished communities of color, where “poor urban women were long associated with hypersexuality” and “over-reproduction.” 60 She claims “many Americans believed ‘ghettos’ were filled with women more prone to unwanted pregnancy and abortion, thus in need of anti-abortion services.” According to Dr. Holland, the anti-abortion movement simultaneously portrayed people of color as victims to be saved and potential threats.61 Eventually, interstate highway systems expanded beyond urban centers and into suburban communities, which allowed CPCs to expand their ground game alongside the growing number of roadside abortion providers.

By the time the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways was complete, 1.4 million American women were procuring legal abortions each year.62 This was a slight increase from the estimated 1.2 million American women who illegally obtained abortions every year in the 1950s and 60s.63 An increase possibly accounted for by population growth and decreased suicide and death rates previously linked to the criminalization of abortions. The automobility of America, alongside interstate infrastructure, fundamentally changed access to abortion care, particularly for women from states with abortion restrictions. Car culture and abortion access became intimately linked. Underground networks referred to abortion procedures as the “Cadillac, Chevrolet, or Rolls-Royce.” 64

The Cadillac, a silent fifteen-minute procedure with no anesthesia, was provided in total anonymity. The Rolls-Royce afforded women post-operation vital monitoring to mitigate the risk of bleeding out for a few extra thousand dollars. These procedures were performed at roadside motels. Of the million or so women obtaining abortions, both legally and illegally, in the latter half of the 20th century, nearly 60,000 drove more than 500 miles to access care. A few hundred women from the West drove more than 2,000 miles.65

Dr. Holland compiled the first history of the anti-abortion movement, which she describes as a national, cultural, and political history with significant regional importance inseparable from “Cold War migrations and transformations” of the American West.66 She posits that “anti-abortion activism was a product of the Cold War.” In the developing territories of the American West, abortion access remained severely restricted, populated by primarily Mormon and Catholic religious communities.67 Fidelity to the American nation in states responsible for nuclear weapons manufacturing was particularly high in the post-war era and is reflected in abortion restrictions today. In Amarillo, the transition from World War II to the Cold War was incessant. The transformation of the Panhandle by military-grade highways entrenched the belief that abortion was a treacherous “Soviety philosophy” long after abortion was legalized.68

Twenty-seven hundred abortion facilities opened in the United States in the five years after Roe passed 69 During that same time period, there were only six hundred CPCs.70 In the remaining forty-five years after Roe’s passing, CPCs proliferated faster than abortion providers. Anti-abortion activists believed if they could persuade people abortion was murder that harmed both the fetus and the mother, then they could “hypothetically stop abortion without changing the law” through misinformation campaigns. 71 A similar tactic to Dickson’s fixated on the highway.

Robert Pearson, the author of How to Start and Operate Your Own Pro-life Outreach Crisis Pregnancy Center, founded the first CPC in the United States in Hawaii in 1967. His manual begins by comparing CPCs to car dealerships. “A car dealer, when he’s advertising, does not list the things his auto won’t do. So why should we say we don’t do abortions?”72 In his seminal text that inspired much of the anti-abortion movement, Pearson advised anti-abortion activists to “choose neutral-sounding names and show women a slide show that includes misinformation about the health risks of abortion.” 73 A sample script for CPC volunteers was included in Pearson’s manual.

QUESTION: Do you do abortions?

ANSWER: Anything you need, we do here.

QUESTION: I want to have an abortion, will you help me?

ANSWER: We have many ways to help a woman and will gladly help you. Have you had a test? We will be glad to do one for you. 74

These deceptive practices persist at CPCs today. Dr. Holland describes CPCs as “more medical, sometimes in performance and practice.” Some CPCs insist staff wear lab coats and provide free STD testing and ultrasounds, despite lacking medical certifications, because as one CPC director explained, “if you can get a lady into an ultrasound room, then ninety percent will carry that baby to term.”75 Reporting from the New York Times documents CPC activists annexing the sidewalk outside of actual abortion clinics, dressed in safety vests that resemble the uniform of clinic escorts, to confuse abortion clinic patients while hoping to provide unproven medical statistics that link abortion to breast cancer, mental health issues, and infertility. 76

Initially, CPCs did not have access to federal infrastructure funding like their segregationist friends who influenced highway design. They just disbursed themselves around them. That changed during the first term of George W. Bush’s presidency. Federal grants doubled and tripled CPC annual operating budgets to promote abstinence-only education. 77 In 2022, the year that Roe fell, CPCs recorded $1.4 billion in revenue and $344 million in government funding.78 Texas now runs the largest alternative to abortion program in the United States. Over $140 million in state funding has been diverted from federal temporary assistance programs for low-income families to crisis pregnancy centers,79 while Texas’ anti-abortion laws closed every abortion clinic in the state. In 2000, CPCs outnumbered US abortion providers two to one. Post Dobbs, CPC infrastructure now outnumbers abortion providers four to one.80

In the summer of 2020, the Texas A&M Univesity system donated a building in the midst of public university student housing to a CPC just outside Amarillo. Advertisements celebrating its grand opening are visible from the interstate near Dickson’s billboard campaign. Publicly, this new CPC location amidst university housing does business as 1330 Coffee. Its name comes from bible verse Numbers 13:30, “Then Caleb silenced the people before Moses and said, ‘We should go up and take possession of the land, for we can certainly do it.’” 81 1330 is owned by Hope + Choice, a CPC affiliate of Carenet, the second-largest anti-abortion organization in the United States, founded by the Christian Action Council in 1975.82 Hope + Choice sounds like a healthcare center that might offer life-saving abortion referrals if necessary. Instead, it offers pro-life counseling, which, as an employee shared with me, “gives women the choice to be hopeful about their pregnancy.”83

It’s unclear how literal Hope + Choice means that the land donated to construct 1330 is dedicated to the repossession of anti-abortion provisions, but a recent YouTube conversation between Hope + Choice CEO Candy Gibbs and Texas Congressman Ronny Jackson and Texas Senator Kevin Sparks suggests as much.84

1330 has a smartphone app for students. I attempted to download the app with my Amarillo 806 area code but was unable to. My geolocation is active in New York, not the Texas Panhandle. An organizer with ARFA downloaded the app instead. After being required to submit excessive personal details, including gender identification, which is increasingly criminalized, the app displayed coffee shop hours, information about praise and worship band auditions, and information about free “discrete” pregnancy testing available in 1330’s basement. Hope + Choice has two other locations in Amarillo: one in the medical district across from the two hospitals in town and the other inside a now-shuttered Planned Parenthood. The six-foot wrought iron gate that kept anti-abortion activists armed with bricks out still surrounds the perimeter.

Hope + Choice will break ground on its fourth location on the Northside of Amarillo later this spring. Today, the Northside of Amarillo is home to Black, Latine, East African, and Southeast Asian refugee communities. The hospital that served Amarillo’s predominantly non-white residents on the North and East sides of town shuttered two decades ago following waves of nearby interstate construction that consolidated routes to Pantex and exported healthcare to white neighborhoods. Among the material services Hope + Choice has promised to provide Northside residents are routine car seat checks with the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT).85

Comparative literature scholar Michael Truscello notes that all infrastructure is first visible as “imaginary government policy, or corporate planning, then as design, then as massive construction, then in operation, then as ruins.”86 The re-emergence of Comstock, a once imaginary policy, and now established tool of the state, regulates people with uteruses as territory destined to be controlled.

CPCs, gendered rest stops, and highway infrastructure are vestiges of white supremacist architecture that render women and non-binary people as natural resources: a scaling vestige of fascism still in the construction phase.

Can highway design be blamed for a backdoor national abortion ban? Not entirely—and yet highways were the defining organizing principle of the twentieth century as reproductive healthcare expanded women’s access to self-determination.87 Highways remain an important tool for white Christian supremacists like Dickson to manipulate. His play for infrastructural control will enter operation swiftly or be diverted entirely, hopefully followed by a swifter demise of the American empire. As a defacto colony, Amarillo embodies amalgamated, malevolent facets of US infrastructure. It is my home and our collective, waking nightmare.

. . .

1 The eight agencies surveilling the rest-stop include: Texas Department of Public Safety, Houston Regional Intelligence Service, Southwest Texas Fusion Center, Northwest Texas Fusion Center, Fusion Center Matrix El Paso - Multi-agency Tactical Response Information Exchange, Dallas Police Department Fusion, Fort Worth Intelligence Exchange, and the Austin Regional Intelligence Center.

2 Anne Elizabeth Moore, “The American Rescue Industry: Toward an Anti-Trafficking Paramilitary.” Truthout, April 8, 2015, https://truthout.org/articles/the-american-rescue-industry-toward-an-anti-trafficking-paramilitary/.

3 The Texas Rangers are a paramilitary force, disbanded after Reconstruction and reconstituted as the primary criminal investigative branch of the Texas Department of Public Safety. Today, the Rangers supervise border security, sexual assault investigations, and intelligence and tactical special operations.

4 Michael Truscello, Infrastructural Brutalism: Art and the Necropolitics of Infrastructure (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2020), 118.

5 Richard T.T. Forman, et al., “Chapter 2: Roads,” in Road Ecology: Science and Solutions (Washington DC: Island Press, 2003), 27.

6 Deena Rymhs, Roads, Mobility, and Violence in Indigenous Literature and Art from North America (New York: Routledge, 2020), 75.

7 Selena Simmons-Duffin and Shelly Cheng, “How Many Miles Do You Have to Travel to Get Abortion Care? One Professor Maps It,” NPR, June 21, 2023, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/06/21/1183248911/abortion-access-distance-to-care-travel -miles.

8 Kimya Forouzan, Amy Friedrich-Karnik, and Isaac Maddow-Zimet, “The High Toll of US Abortion Bans: Nearly One in Five Patients Now Traveling Out of State for Abortion Care,” Guttmacher Institute, December 7, 2023, https://www.guttmacher.org/2023/12/high-toll-us-abortion-bans-nearly-one-five-patients-now-traveling-out state-abortion-care.

9 Truscello, 136.

10 Jennifer L. Holland, “‘Survivors of the Abortion Holocaust’: Children and Young Adults in the Anti-Abortion Movement.” Feminist Studies 46, no. 1 (2020): 74–102, https://doi.org/10.1353/fem.2020.0000.

11 Holland, Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (Oakland: University of California Press, 2020), 5.

12 NARAL Pro-Choice America Research Team. “Anti-Choice Extremist Mark Lee Dickson’s Ties to Texas Senate Bill 8.” Memo, September 1, 2021. https://reproductivefreedomforall.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Memo-on-Mark-Lee-Dickson.pdf.

13 Emily Wax-Thibodeaux, “Mark Lee Dickson Paved the Way for the Texas Abortion Ban, One Small Town at a Time,” Washington Post, September 17, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/mark-dickson-texas-abortion-ban/2021/09/16/bb773a0a-0c02-1 1ec-a6dd-296ba7fb2dce_story.html.

14 Steven Ertelt, “Prohibiting Abortion Trafficking Will Help Pregnancy Centers in the Texas Panhandle.” LifeNews.com, February 21, 2024. https://www.lifenews.com/2024/02/21/amarillo-texas-measure-would-stop-trafficking-teens-to-other-states -for-secret-abortions/.

15“Sanctuary Cities for the Unborn (Incorporated Cities),” Sanctuary Cities for the Unborn, accessed December 18, 2023, https://sanctuarycitiesfortheunborn.org/incorporated-cities.

16 Caroline Kitchener, “Highways Are the Next Anti-abortion Target. One Texas Town Is Resisting,” Washington Post, September 1, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/09/01/texas-abortion-highways/.

17 “Sanctuary Counties for the Unborn,” Sanctuary Cities for the Unborn, accessed April 12, 2024, https://sanctuarycitiesfortheunborn.org/counties.

18 Mark Lee Dickson, email to author, March 3, 2024.

19 Rosemary Westwood, “Standard Pregnancy Care Is Now Dangerously Disrupted in Louisiana, Report Reveals,” NPR, March 19, 2024, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2024/03/19/1239376395/louisiana-abortion-ban-dangerously-di srupting-pregnancy-miscarriage-care.

20 Forman, 29.

21 Ibid.

22“A Timeline of Contraception | American Experience,” PBS, accessed March 22, 2024, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-timeline/.

23 Smithsonian Postal Museum, “Anthony Comstock,” accessed April 14, 2024, https://postalmuseum.si.edu/exhibition/behind-the-badge-postal-inspection-service-duties-and-history-hist ory/anthony-comstock.

24 Sanctuary Cities for the Unborn, “Sanctuary Cities for the Unborn - Comstock Ordinances,” accessed April 12, 2024. https://sanctuarycitiesfortheunborn.org/countiess.

25 Rachel K. Jones and Amy Freidrich-Karnick, “Medication Abortion Accounted for 63% of All US Abortions in 2023—An Increase from 53% in 2020 | Guttmacher Institute,” March 12, 2024, https://www.guttmacher.org/2024/03/medication-abortion-accounted-63-all-us-abortions-2023-increase-53 -2020.

26 Eleanor Klibanoff, “How an Old Law Found New Life in Lawsuit Seeking to Revoke Approval of Abortion Pill,” The Texas Tribune, March 20, 2023, https://www.texastribune.org/2023/03/20/texas-fda-abortion-pill-comstock-act/.

27 Shoshanna Ehrlich, “The Comstock Act Is a Backdoor Approach to a National Abortion Ban—And Justices Alito and Thomas Are Interested,” Ms. Magazine, April 1, 2024, https://msmagazine.com/2024/04/01/comstock-act-abortion-pills-mifepristone-supreme-court/.

28 Steven Shroeder, “On Learning to See Nothing: The Institution of Pantex”(Popular Culture Association, Las Vegas, Nevada, 1996).

29 “Federal Aid Road Act of 1916: Building The Foundation | FHWA,” accessed March 11, 2024, https://highways.dot.gov/public-roads/summer-1996/federal-aid-road-act-1916-building-foundation#:~:text =The%20Federal%20Aid%20Road%20Act,were%20designed%20and%20constructed%20properly.

30 Alex Hunt and Dan Kerr, “The Quitaque Killings,” The Journal of the West 51, no. 2 (Spring 2012): 7–15.

31“First American Birth Control Clinic (The Brownsville Clinic), 1916 | Embryo Project Encyclopedia,” October 11, 2019, https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/first-american-birth-control-clinic-brownsville-clinic-1916.

32 A.G. Mojtabai, Blessèd Assurance: At Home with the Bomb in Amarillo, Texas, First Edition (Syracuse University Press, 1997), 26.

33 Amarillo Planned Parenthood, “Oral Histories Regarding Sex Education and Birth Control” (Oral History Project, 2008), Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum Research Collection.

34 Mojtabi, 68.

35 Texas Department of State and Health Services, “Pantex Nuclear Weapons Facility,” accessed April 7, 2024.

36 Shroeder, 2.

37 Shroeder,10.

38 Donny Vernon, Interview with Pete Gilvin, Oral History Project, November 8, 1985, Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum.

39 Shroeder, 4.

40 Shroeder, 8.

41 “National Interstate and Defense Highways Act (1956) | National Archives,” February 8, 2022, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/national-interstate-and-defense-highways-act.

42 Michael Casey, “Texas Wildfires Forces Shutdown at Nuclear Weapon Facility. Here Is What We Know,” AP News, February 28, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/texas-wildfires-nuclear-facility-pantex-16bfa90f49b65b604f63744a9aee3b97.

43 Mojtabai, 26.

44 Stephen Simpson, “Public Blasts Texas Agencies, Regulators for Poor Communication and Oversight at Wildfire Hearings,” The Texas Tribune, April 4, 2024, https://www.texastribune.org/2024/04/04/texas-wildfires-utilities-hearings/.

45 Lucie Genay, Under the Cap of Invisibility: The Pantex Nuclear Weapons Plant and the Texas Panhandle (University of New Mexico Press, 2022).

46 Anderson, H. Allen. “Amarillo, TX.” Texas State Historical Association, September 20, 2023. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/amarillo-tx.

47 Kitchener, “Highways Are the Next Anti-abortion Target.”

48 Sara Ahmed, “Affective Economies,” Social Text 22, no. 2 (May 14, 2004): 117–39, https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/4/article/55780.

49 Brendan Pierson and Brendan Pierson, “Court Upholds Texas Parental Consent Law for Birth Control,” Reuters, March 12, 2024, sec. Government, https://www.reuters.com/legal/government/court-upholds-texas-parental-consent-law-birth-control-2024-0 3-12/.

50 Julie Lee et al., “Roadblock to Care: Barriers to Out-of-State Travel for Abortion and Gender Affirming Care” (Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, July 18, 2023), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c1bfc7eee175995a4ceb638/t/64b04a5113f1c43496dc48cc/16892 74961669/Roadblock+to+Care.pdf.

51 Abigail R. A. Aiken et al., “Association of Texas Senate Bill 8 With Requests for Self-Managed Medication Abortion,” JAMA Network Open 5, no. 2 (February 25, 2022): e221122, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1122.

52 Mark Lee Dickson, “Amarillo Sanctuary City for the Unborn Ordinance” (Sanctuary Cities for the Unborn, December 29, 2023), https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/4b2b0d23-d175-4bfb-a8d9-71911a3ad695/downloads/amarillo-scftu-or dinance%20(12-29-2023).pdf?ver=1710240907286.

53 Sarah Marshall, You’re Wrong About: The “Pro-Life” Movement with Megan Burbank on Apple Podcasts, accessed March 22, 2024, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-pro-life-movement-with-megan-burbank/id1380008439?i=1000 642970777.

54 Holland, 4.

55 “Environment and Natural Resources Division | History of the Federal Use of Eminent Domain,” United States Department of Justice, April 13, 2015, https://www.justice.gov/enrd/condemnation/land-acquisition-section/history-federal-use-eminent-domain.

56 “How Interstate Highways Gutted Communities—and Reinforced Segregation,” HISTORY, September 21, 2023, https://www.history.com/news/interstate-highway-system-infrastructure-construction-segregation.

57 T.R. Witcher, “How the Interstate Highway System Connected — and in Some Cases Segregated — America,” American Society of Civil Engineers, July 15, 2021, https://www.asce.org/publications-and-news/civil-engineering-source/civil-engineering-magazine/article/20 21/07/how-the-interstate-highway-system-connected--and-in-some-cases-segregated--america.

58 Ginger Strand, “Chapter 3: The Cruelest Blow,” in Killer on the Road: Violence and the American Interstate (Discovering America) (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012), 98.

59 Truscello, 138.

60 Holland, 124.

61 Holland, 161.

62 Center for Disease Prevention, “Abortion Surveillance -- United States, 1992,” accessed April 14, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00041486.htm#:~:text=Results%3A%20In%201992%2C% 201%2C359%2C145%20abortions,15%2D44%20years%20of%20age.

63 Rachel Benson-Gold, “Lessons from Before Roe: Will Past Be Prologue? | Guttmacher Institute,” September 22, 2004, https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/03/lessons-roe-will-past-be-prologue.

64 Tia Lessin and Emma Pildes, The Janes, Documentary (HBO Documentary Films, Pentimento Productions, 2022).

65 Ibid.

66 Holland, 3.

67 Holland, 9.

68 Mojtabai, 94.

69 Willard Cates et al., “The Public Health Impact of Legal Abortion: 30 Years Later,” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 35 (January 1, 2003): 25–28, https://doi.org/10.1363/3502503.70 Holland, 124.

71 Holland, 123.

72 Hayley Malcolm, “PREGNANCY CENTERS AND THE LIMITS OF MANDATED DISCLOSURE,” Columbia Law Review 119, no. 113 (May 2019), https://columbialawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Malcolm-PREGNANCY_CENTERS_AND_TH E_LIMITS_OF_MANDATED_DISCLOSURE.pdf.

73 Carly Thomsen, Carrie N. Baker, and Zach Levitt, “Opinion | Pregnant? Need Help? They Have an Agenda.,” The New York Times, May 12, 2022, sec. Opinion, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/05/12/opinion/crisis-pregnancy-centers-roe.html. 74 Thomsen, Pregnant?

74 Thomsen, Pregnant?

75 Holland, 128.

76 Thomsen, “Pregnant?”

77 Thomas Edsall, “Grants Flow To Bush Allies On Social Issues,” Washington Post, March 22, 2006, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/03/21/AR2006032101723.html.

78 Carter Sherman, “Anti-Abortion Centers Raked in $1.4bn in Year Roe Fell, Including Federal Money,” The Guardian, February 14, 2024, sec. World news, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/feb/14/anti-abortion-centers-funding.

79 Carter Sherman, “States to Award Anti-Abortion Centers Roughly $250m in Post-Roe Surge,” The Guardian, December 28, 2023, sec. World news, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/dec/28/anti-abortion-pregnancy-crisis-centers-taxpayer-money-roe.

80 Thomsen, “Pregnant?”

83 Interview with Mallory Cockrell, Hope + Choice Executive Assistant, March 5, 2024.

84 Candy Gibbs, Episode 4: Faith in Government, YouTube (Hope + Choice, 2024).

85 Texas Department of Transportation, “Child Passenger Safety,” accessed April 22, 2024, https://www.txdot.gov/safety/traffic-safety-campaigns/child-passenger-safety.html.

86 Truscello, 26.

87 Truscello, 129.